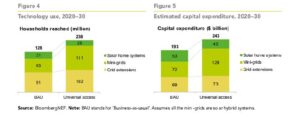

About 238 million households will need to gain electricity access in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and island nations by 2030 to achieve universal electricity access.

Of this, Mini-grids can serve almost half of this total – an estimated 111 million households with a capital investment of $128 billion, 78 per cent higher than the estimated capital investment in a business-as-usual scenario.

This is contained in the ‘State of the Global Mini-grids Market Report 2020’, released by Mini-grids Partnership and published by the SE4All and Bloomberg NEF earlier today.

According to the report, ambiguous rural electrification policies, lack of flexibility in setting mini-grid tariffs, and complex and lengthy licensing processes are some of the major challenges that hinder mini-grid projects.

“There is also growing public and political sensitivity to electricity tariffs, making flexible tariff setting difficult (e.g., in Tanzania ). In contrast to Nigeria, many governments lack regulations that protect isolated mini-grids if the main grid arrives.

“Without such regulations, the state may expropriate mini-grid assets with minimal compensation, or in the worst case, they can be stranded. Even when there are regulations in place, governments and state-owned utilities do not always enforce them,” it said.

In a business-as-usual scenario, mini-grids would require $72 billion, in addition to an investment of $69 billion required for grid extensions.

The latter would serve a larger number of households as high-density areas would be prioritized for electrification.

In total, universal energy access would require capital investment of about $243 billion between 2020 and 2030.

Solar home systems would be the least-cost option to offer electricity access to some 25 million households from a capital investment of $42 billion.

The authors estimate that mini-grids can supply electricity to approximately 81 million households without electricity access in Sub-Saharan Africa through to 2030.

This, according to them will require a capital investment of about $93.1 billion.

“Within Sub-Saharan Africa, Ethiopia is the largest potential market. Here, electricity access has improved relatively quickly in parallel with the nation’s economic boom of the last few years, although nearly 60 per cent of the population of 109 million did not have access to electricity at the end of 2018.

The government launched its first tender programme to install 25 solar hybrid mini-grids in 2019.

Nigeria has the second largest number of potential opportunities in Sub-Saharan Africa and the largest within West Africa, given the size of its population without access to electricity.

Its electricity grid is notoriously unreliable, driving the vast majority of people and businesses to rely on diesel generators, and increasingly, also solar and storage.

The country has set up a robust regulatory environment to make mini-grid projects viable. Its two recent results-based financing (RBF) programmes (i.e., performance-based grant and minimum subsiidy tender) are likely to provide direction to other Sub-Saharan African countries on how best to target subsidy mechanisms to scale mini-grid market.

Asian countries have improved electricity access significantly, reaching an average access rate of 94 per cent at the end of 2018.

The authors estimate that mini-grids are the most suitable approach for the remaining 29 million households in the region that remain without access to electricity and for which a total capital investment of approximately $33 billion will be required.

In 2018, small island nations, namely the Pacific and Caribbean islands, had a total unserved population of some 15.9 million. This represents only 1.7 per cent of the global population without access.

“Three out of the 17 island nations studied in this report accounted for 85 per cent of all mini-grid connections in the region. Haiti achieved 589,000 connections, followed by 463,000 in Papua New Guinea and around 78,000 in the Dominican Republic.

This technology is the most suitable option for most low- and medium-density areas, and more affordable for low-income families than alternative option.

Solar home systems, mostly small and basic ones, would proliferate where electricity access gaps persist. But still we would be falling short of universal access.

As of February 2020, there were 5,544 installed mini-grids identified in the mini-grid asset database built in this research, of which 60 per cent and 39 per cent were in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa respectively while generation capacity totalled 2.37GW.

Solar are the most dominant form of modern mini-grids installed today, and many mini-grid programmes are led by governments that are eager to promote them.

Hydro mini-grids continue to be common where resources are available (e.g., in parts of Tanzania and Nepal).

In Sub-Saharan Africa, Senegal and Tanzania have 227 and 209 mini-grids installed respectively. In Senegal, at least 63 projects were built under the Energising Development (EnDev) programme.

In Asia, India leads with 1,792 mini-grids, followed by 1,061 in Indonesia and 326 in the Philippines.

The latter two countries have thousands of islands that have no main grid connections and are either reliant on minigrids or have no access to electricity,” the report added.