By Ayobami Adedinni

It is a Monday morning rush and kids are on their way to school – at least some of them – not Maryam. She has to help her mother in gathering firewood to make breakfast for her and her siblings in an unventilated kitchen before she goes to school at a time when her classmates have already had two lessons.

Most times, she dozes off immediately she gets to class. Maryam is just 9.

Tito, her school mate and friend, who lives in a 2 bedroom apartment with her parents, has not been to school for a week. She had been coughing in the past few weeks and was told to stay at home for treatments. Her father is unemployed and her mother is a public primary school teacher who has been owed backlog of salary by the government.

They had resorted to firewood use to “cut costs”- because they cannot afford the use of liquefied petroleum gas, or L.P.G.

Sadly, this deadly scenario is not peculiar to Maryam and her friend’s family.

The World Health Organisation, WHO, reports that household air pollution almost doubles the risk for childhood pneumonia, and attributed more than a half the deaths among children less than 5 years old from acute lower respiratory infections to smoke from indoor fires.

Evidence from WHO survey on the global burden of disease shows that nearly 600,000 Africans die annually and millions more suffer from chronic illnesses caused by air pollution from inefficient and dangerous traditional cooking fuels and stoves such as wood, charcoal, crop waste, dung, coal, and potentially dangerous and polluting modern fuels, such as kerosene.

According to the World Bank, more than 700 million Africans (82 per cent) depend primarily on solid fuels for their cooking needs, and the penetration of clean cooking technologies in this population is negligible (<0.1 per cent).

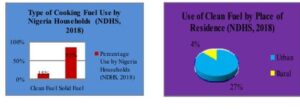

Specifically, the Nigerian Demographic Health Survey (NDHS) 2018 says only about 15 per cent of households in Nigeria use clean fuel for cooking while majority of the households use solid fuel for cooking, the differential in the place of residence showed that there is a wide gap in the use of clean fuels between Urban (about 27 per cent) and Rural households (4 per cent).

This shows that the use of clean fuels in both places of residence is very low.

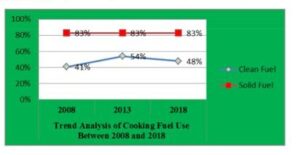

A clearer view of the situation can be found in the trend analysis evaluated by Petrolgas Report using the NDHS report of 2008, 2013 and 2018.

Over the 10 year period, it was discovered that the use of solid fuels such as wood, coal/lignite and charcoal has nearly remained the same and more commonly used in rural areas as a consistent usage percentage of about 83 per cent of the households were recorded in the three different reports while the trend in the urban households took a different turn, as there was an increase in the use of clean fuels from about 41 per cent of the households in 2008 to an increased rate of about 54 per cent in 2013 and to a decreased rate of about 48 per cent in 2018.

This analysis shows that the use of clean cook fuel is still low and therefore, an Improved Cook stove (ICS) intervention in Nigeria could serve a large market across both rural and urban areas.

According to the Journal of Health Communication (2015), ongoing research highlights that clean fuels are highly desired and when people have access to very clean fuels, they use it consistently and stop using their traditional stoves.

However, penetration of clean cooking solutions remain limited, and efforts to promote their adoption face substantial obstacles, including consumers’ limited willingness to fully adopt new cooking solutions and limited ability to pay higher cost.

“Energy poverty has the face of a woman because 80 per cent of the energy needs will definitely be that of the women. How many women can afford clean gas when it is about N4,000 ($11)for a 12kg cylinder?” Anita Nana Okuribido, President, Women in Renewable Energy told our correspondent recently.

She continued; “So, a lot of women have resorted to the use of kerosene which emits poisionous substances. As I speak with you, 120 million Nigerians are scavenging for energy.

“It’s why a lot of women have lung diseases with their children. This is because when they’re cooking , children are around their mothers.”

It should be noted that the Sustainable Development Goal, SDG 7, of the United Nations Development Program aims to ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all by 2030.

“The Nigerian cooking sector increasingly represents an attractive niche market for the private sector as reflected by increasing entry over the past few years of social enterprises, multinationals, impact investors, and carbon finance projects, including the launch of several large-scale, Africa-based manufacturing facilities for cleaner and more efficient biomass stoves and fuels,” the World Bank in a 2014 report said.

Way forward

However, Bassey Essien, executive secretary, Nigerian Association of Liquefied Petroleum Gas Marketers, NALPGAM told Petrolgas Report that the provision of necessary environment infrastructure is needed to boost the sector.

In his words, “Government should make available incentives that would encourage people to leave firewood, charcoal, kerosene and come to LPG. But what are these incentives? You know how much cylinders, even a table top burner, hoses and the rest cost.

“For someone who is just starting, for you to put everything together, if you are lucky, you spend a minimum of N25, 000 ($68). And yet someone gathers firewood to start cooking because the person has nothing to lose. If you now want them to migrate to LPG, there needs to be encouragement.

“Frankly speaking, if we say we have a population of 190 million and less than 40 million are using gas, what are we talking about?” he retorted.

The investment opportunities, he said, are there. “The only thing needed is the enabling environment to encourage people. Most of the gas being used is in the major cities. An average person in the rural area does not have them.

“What is truly needed is the right encouragement and incentives. If we have enough awareness, there will be a ripple effect in the demands for the product. And once there is a high demand, there will be supply,” he added.

Also, the World Bank in its report suggests the public, donor, and NGO sectors must complement private-sector stove and fuel distribution initiatives with intensive consumer awareness efforts similar to the hand washing, public defecation, and vaccination campaigns already familiar in the public health setting that can educate end users about the harms of stove and fuel stacking; encourage outdoor cooking and better indoor ventilation; and train end users on optimal cooking techniques, including fuel preparation (for instance, biomass drying prior to cooking), kindling, fire tending, and optimal heat adjustment and dish sequencing for best fuel efficiency and emissions.

Addressing these barriers will require substantially higher private and public investments, greater stakeholder coordination, and improved information to help decision makers learn from past experience, innovate, and measure progress in what continues to be a very opaque and fragmented sector.