This is a continuation of the The Gas-to-Power Nexus in Nigeria series

Current state of Gas-to-Power Projects

With private sector involvement, there have been significant improvements in the gas market. Some notable actors and projects include:

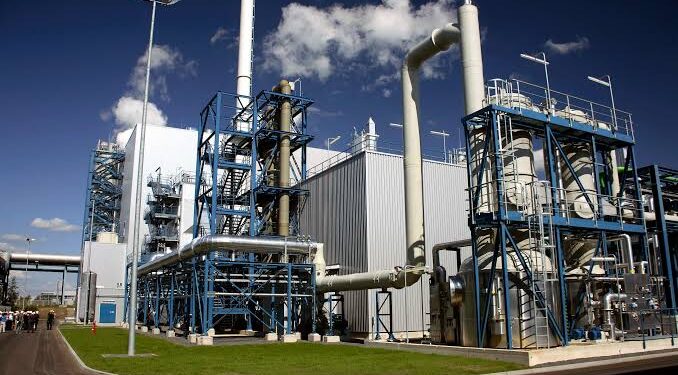

Shell Nigeria Gas (SNG) completed the Agbara-Ota Capacity Project in 2019. The gas plant is reported to have increased the country’s gas production and distribution capacity by over 150%.

Pan Ocean Oil Corporation recently completed the two phases of the Ovade-Ogharefe Gas Processing Plant.

The biggest gas pipeline project in Nigeria-the Obiafu-Obrikom to Oben (OB3) Gas Pipeline is scheduled for completion in 2021.

The ongoing Ogidigben Gas Revolution Industrial Park owned by the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC)

Ajaokuta-Abuja-Kano-Kaduna (AKK) Gas Pipeline Project which has attracted support from China’s Sinosure and a group of Chinese financial institutions to the tune of $2.3 billion and was flagged off in June 2020 by President Mohammadu Buhari

Dangote Complex- $2 billion fertilizer plant with a 3.0 MTPA capacity which depends on natural gas as feedstock.

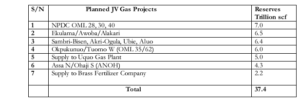

Specifically related to gas-to-power, proposed and ongoing plans/projects include:

Gas-to-Power Challenges in Nigeria

“About 145 to 150 BCM gas is flared per year globally, enough to produce 750 billion kwh of power, which is more than the annual power consumption in the entire African continent”.

Gas is the primary source of power generation in Nigeria, and the power sector in the country has been affected by insufficient gas supplies to cater to the four gas-fired thermal successor generation companies, the anticipated National Integrated Power Project (NIPP) expected to rely completely on gas, and anticipated gas-fired power generation.

Despite the abundant gas resources currently in place in Nigeria, placing it as the ninth largest gas producer in the world, a significant portion of the country’s gas resources have not been converted to electric power.

The insufficiency of gas supplies has resulted in Gas Supply Agreements being made on ‘reasonable endeavours’ or ‘best endeavours’ basis, rather than gas supplies being made on definite quantities governed by stiff take-or-pay provisions.

This situation, in turn, has negatively affected the bankability of gas and power projects in Nigeria. The Key challenges in the gas-to-power value chain are highlighted below

Key challenges

- Gas Availability (Demand growth v Feed Gas Supply) stemming from inadequate capital investment

Lack of adequate capital for the needed upstream oil and gas developments owing to the competing political and socio-economic objectives of the government to which the government has to devote its financial resources and is therefore unable to sufficiently fund its interests under the respective Joint Venture/Joint Operating Agreements via cash calls, thus resulting in investment and infrastructural development challenges.It is estimated that almost 2,000 MW of power is stranded due to gas unavailability, despite the additional 1,000 MW that is also estimated to be stranded due to non-gas related constraints.

- Gas Deliverability (Inadequate gas transportation and processing infrastructure across the value chain). There is currently a dire lack of adequate infrastructure to transport gas to power producers coupled with insufficient domestic gas price incentives. Gas Pipeline vandalism exists as a barrier to gas-to-power projects. For example, although repairs on the Escravos-Lagos pipeline that was vandalised in early March 2015 were completed by the end of the month, power plants were deprived of some 1500 MW, contributing to electricity shortages and low generation output.

- Legal and Regulatory Impediments

There is a misalignment between the legal, regulatory and policy framework across the gas-to-power value chain resulting in a lack of cooperation among key stakeholders in the gas-to-power value chain and a disjointed approach towards the regulation of domestic supply of gas in the country.

There are also regulatory and institutional misalignments between the domestic gas supply industry and the electric power market and policy inconsistencies. For example, differing approaches are employed with regard to price regulation and resource allocation; a major impediment being the inconsistency between the power sector’s price and economic regulation approach which is an incentive based model in comparison with the gas supply industry which remains subject to the traditional cost of service/rate of return model.

In addition, another notable example of divergence is with regard to the Nigerian Gas Transportation Network Code recently released to harmonise the contractual regime for the transportation of gas which was previously governed by gas transportation agreements that made provisions for delivery of accumulated gas at delivery points via dedicated gas transportation and distribution infrastructure. There is a non-alignment of the Code with existing contracts for power generation, thus creating inconsistencies in the contractual framework for gas to power transactions from the perspective of gas transportation for power projects.

Of critical note is the fact that the regulatory and fiscal reforms in the oil and gas industry remain pending with the delay in the passage of the Petroleum Industry and Governance Bill which has dire implications on the government’s aspirations towards the attainment of a coherent gas-to-power value chain. - Security, Affordability, Reliability, Commerciality and Pricing of Gas Supply for Power Generation. The power sector in Nigeria is fraught with a debacle of issues across the value chain which have in effect resulted in a liquidity crisis in the sector. The main concern that has plagued the industry since its privatisation in 2013 is the lack of truly cost reflective tariffs, emanating from a series of issues that have resulted in a negative domino effect on the industry. These issues include:

- Low electricity generation as a result of network constraints in addition to gas infrastructure and pricing issues.

- Baseline Loss Studies (BLS) data as at the time of privatisation were not fed through into the Multi-Year-Tariff-Order in operation, for tariffs to reflect current realities.

- The sculpted nature of the tariffs which allow for under recovery in the early years and over recovery in later years with no adequate means of funding the gap based on the lack of credibility of the Distribution Companies who exist as the last mile agents in the value chain.

- Non-implementation of the various minor reviews which has not led to a ‘true-up’ or ‘true-down’ of the tariffs to reflect current realities based on changes in certain parameters such as generation capacity, inflation, exchange rates and gas costs, foreign exchange pass through costs not recoverable via end-user tariffs.

- Cost recovery and pricing mismatch based on the fact that the pass through costs from the Power Purchase Agreements (PPA’s) between the Nigerian Bulk Electricity Trader (NBET) and the Generation Companies (GenCos) to the Vesting Contracts between NBET and the DisCos are not recoverable via the MYTO tariffs.

- MDA (Ministries, Departments and Agencies) debts running into trillions of Nigerian Naira and not reflected in the collection loss component of the Aggregate Technical, Commercial and Collection (ATC&C) Losses factored into end-user tariffs.

- Lack of willingness to pay by end-use customers as some still view electricity as a social good.

- Technical Losses, Billing Inefficiencies and Electricity Theft leading to increased ATC&C losses, etc

The cumulative effect of the above listed issues which are not exhaustive has hindered the ability of the DisCos to fulfil their market remittance obligations to the value chain as the last mile collection agents of the industry.

On the gas end of the value chain, the shortage of gas supply continues to prevent the availability of new gas-fired power stations to generate sufficient amounts of electricity. In addition, the lack of an appropriate gas-pricing framework represents a major impediment to the commerciality of gas for power projects, leaving industries with no other option but to self-generate.

By legislation, the Federal Government is permitted to approve the price at which gas is sold domestically which may be viewed as being contrary to international best practice, given the high degree of what has been termed as ‘state controlled’ pricing.

Gas producers do not comply their Domestic Gas Supply Obligations (DGSOs) in flagrant disregard of the National Domestic Gas Supply and Pricing Policy 2008 and the National Domestic Supply and Pricing Regulations 2008 and instead opt for the exportation of natural gas.

Participation in the international gas market is usually a juicy sell to domestic gas producers, due to the investment-friendly prices. Gas companies will rather explore LNG export to the international market where there are preferable contract terms and appropriate levels of regulatory certainties and guaranteed reasonable return on investments.

This system/practice pushes unrealistically low prices for the domestic market and has created a huge shortage of gas in relation to domestic demand which has in effect halted industrial development across several sectors of the economy, notably the power sector.

In addition, the cost of building additional infrastructure to sell to the domestic market, does not make economic sense to gas producers who do not have to contend with such challenges in the international market.

Another disincentive is the fact that in the domestic gas market, gas producers will need to identify credible off-takers beforehand, unlike in the international market where most of the gas is traded in the spot market.

Nevertheless, optimistic propositions exist to the effect that:

– The illiquidity in the Power sector is addressed and holistic pricing reforms are set in place which is currently ongoing;

– For the other markets, the FG introduces reforms for the removal of price subsidy to foster a free market interplay such as the recent Market Based Pricing Regime for Premium Motor Spirit (PMS) Regulations, 2020 released by the Petroleum Product Pricing Regulatory Agency (PPPRA) on the 4th of June 2020. The Regulations provides for a system which seeks to deregulate the pricing regime in the sector.

The totality of the challenges impacts the commercial viability of gas utilisation projects, most of which are currently operating on a ‘best-endeavour’ basis hinged on the non-enforcement of securitisation terms agreed between parties, occasioned by the all-round liquidity impediments across the gas-to-power value chain.